May 21, 20175:00 AM ET- From Heard on Weekend Edition Sunday – JON HAMILTON

It took an explosion and 13 pounds of iron to usher in the modern era of neuroscience.

In 1848, a 25-year-old railroad worker named Phineas Gage was blowing up rocks to clear the way for a new rail line in Cavendish, Vt. He would drill a hole, place an explosive charge, then pack in sand using a 13-pound metal bar known as a tamping iron.

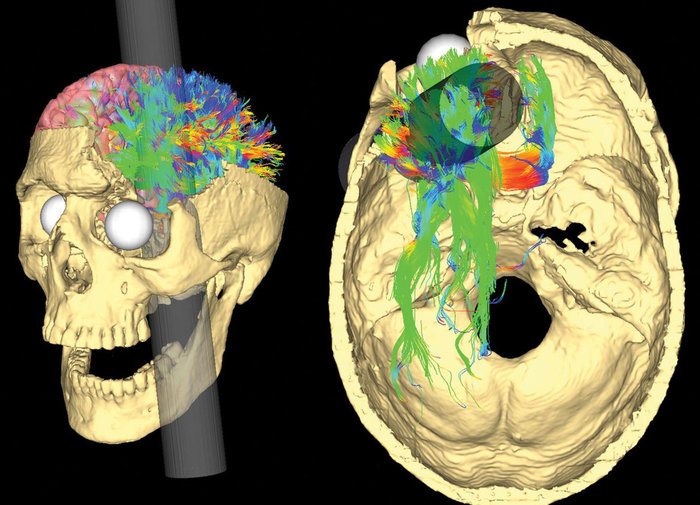

But in this instance, the metal bar created a spark that touched off the charge. That, in turn, “drove this tamping iron up and out of the hole, through his left cheek, behind his eye socket, and out of the top of his head,” says Jack Van Horn, an associate professor of neurology at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California.

Gage didn’t die. But the tamping iron destroyed much of his brain’s left frontal lobe, and Gage’s once even-tempered personality changed dramatically.

“He is fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity, which was not previously his custom,” wrote John Martyn Harlow, the physician who treated Gage after the accident.

This sudden personality transformation is why Gage shows up in so many medical textbooks, says Malcolm Macmillan, an honorary professor at the Melbourne School of Psychological Sciences and the author of An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage.

“He was the first case where you could say fairly definitely that injury to the brain produced some kind of change in personality,” Macmillan says.

And that was a big deal in the mid-1800s, when the brain’s purpose and inner workings were largely a mystery. At the time, phrenologists were still assessing people’s personalities by measuring bumps on their skull.

Gage’s famous case would help establish brain science as a field, says Allan Ropper, a neurologist at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

“If you talk about hard core neurology and the relationship between structural damage to the brain and particular changes in behavior, this is ground zero,” Ropper says. It was an ideal case because “it’s one region [of the brain], it’s really obvious, and the changes in personality were stunning.”

So, perhaps it’s not surprising that every generation of brain scientists seems compelled to revisit Gage’s case.

For example:

- In the 1940s, a famous neurologist named Stanley Cobb diagrammed the skull in an effort to determine the exact path of the tamping iron.

- In the 1980s, scientists repeated the exercise using CT scans.

- In the 1990s, researchers applied 3-D computer modeling to the problem.

- And, in 2012, Van Horn led a team that combined CT scans of Gage’s skull with MRI scans of typical brains to show how the wiring of Gage’s brain could have been affected.

“Neuroscientists like to always go back and say, ‘we’re relating our work in the present day to these older famous cases which really defined the field,’ ” Van Horn says.

And it’s not just researchers who keep coming back to Gage. Medical and psychology students still learn his story. And neurosurgeons and neurologists still sometimes reference Gage when assessing certain patients, Van Horn says.

“Every six months or so you’ll see something like that, where somebody has been shot in the head with an arrow, or falls off a ladder and lands on a piece of rebar,” Van Horn says. “So you do have these modern kind of Phineas Gage-like cases.”

Van Horn JD, Irimia A, Torgerson CM, Chambers MC, Kikinis R, et al./Wikimedia

There is something about Gage that most people don’t know, Macmillan says. “That personality change, which undoubtedly occurred, did not last much longer than about two to three years.”

Gage went on to work as a long-distance stagecoach driver in Chile, a job that required considerable planning skills and focus, Macmillan says.

This chapter of Gage’s life offers a powerful message for present day patients, he says. “Even in cases of massive brain damage and massive incapacity, rehabilitation is always possible.”

Gage lived for a dozen years after his accident. But ultimately, the brain damage he’d sustained probably led to his death.

He died on May 21, 1860, of an epileptic seizure that was almost certainly related to his brain injury.

Gage’s skull, and the tamping iron that passed through it, are on display at the Warren Anatomical Museum in Boston, Mass.