REGARDLESS OF REDESIGNED HELMETS AND RULE CHANGES, BRAINS TAKE THEIR FAIR SHARE OF HITS; IT’S THE NATURE OF FOOTBALL.

Kyle Wood, FSU Staff Writer

The brain is the quarterback of the body. It calls the shots, knows the playbook and motions for an audible when things don’t go as planned. The brain is the body’s franchise player.

Much like a quarterback, it must be protected. Regardless of redesigned helmets, rule changes and extra blockers in the backfield, quarterbacks and brains alike take their fair share of hits; it’s the nature of football.

Everyone likes to see a bone-crushing, game-changing hit.

Fans crave it, coaches love it, players feed off of it – but the brain can’t take it. The same violence that drives the most popular sport in the United States may bring about its downfall as brain injuries pile up and researchers point their fingers at the multi-billion-dollar industry known as the NFL.

Nauseating neurological numbers

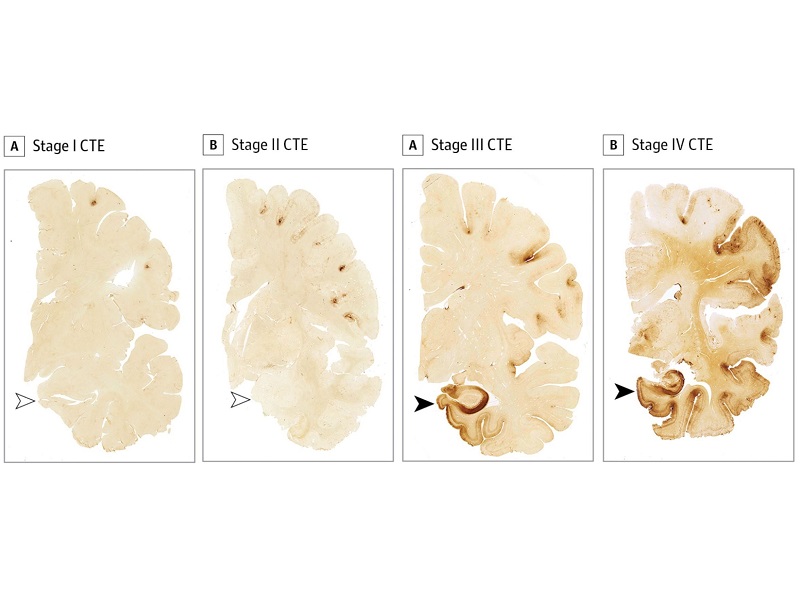

In recent years, research on Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) has brought to light the traumatic effects of repeated blows to the head, seen chiefly in American football. The degenerative brain disease has been a subject of conversation around football leagues from Pee Wee to the NFL. As studies reveal the gruesome effects of the gridiron, growing concerns have arisen regarding the future of the sport.

In July of 2017, Ann McKee, a neuropathologist from Boston University, published extensive research in the Journal of the American Medical Association addressing the high percentage of football players found with CTE. Of 111 former NFL players’ brains tested posthumously, 110 were neuropathologically diagnosed with the disease. However, there certainly was a selection bias as the majority of the brains submitted were by families who had noticed that the men were exhibiting symptoms of CTE. These symptoms included memory loss, rage, mood swings and potential suicidal ideation

Repetitive hits to the brain have an adverse effect on brain tissue, and result in the buildup of tau, a protein found in the brain. The disease negatively affects the superior frontal cortex, which drives cognitive and executive functions as well as working memory and reasoning. The amygdala, which controls emotions, aggression, anxiety and mammillary bodies–which is integral in memory formation–is also damaged as a direct result of CTE.

A common misconception is that concussions cause CTE. However, it’s the repetitive helmet-to-helmet hits, many of which are sub-concussive, that are the culprit. Concussions, similarly to CTE, are a by-product of this trauma.

Despite the explosion of information, there is still a lot that is unknown about the disease.

“One of the problems is we don’t fully understand all the factors involved. One of the issues is that information is still being collected on this Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy,” Dr. J. Lucas Koberda MD, PhD said.

Koberda, a Tallahassee-based neurologist, noted that genetic predispositions, different types of head trauma and variances in position all may affect CTE development. One of the reasons much is still unknown is because the disease can only be diagnosed after death.

“At the moment of a clinical evaluation, you can only say if someone has memory problems, cognitive and behavioral problems, and the degree of that, but we cannot conclude that this is CTE yet because they are still alive so we have to wait for postmortem analysis in those cases,” Koberda said.

The neurons that are destroyed as a result of repeated brain trauma are replaced by the degenerative protein, tau. Koberda noted that neuro-feedback and experimental light therapy could replace the lost neurons and reverse the effects of CTE.

In the past three years alone, Koberda has seen and evaluated more than 100 former NFL players, at their request, for cognitive and behavioral problems observed.

“I’ve seen a sizeable number of NFL players who are coming to my office because of neurological problems including memory issues.”

Traumatic testimony and blood money

The thousands of hits that slowly deteriorate the brains of football players has many of them struggling to recognize themselves, their families and even the game that some paid the ultimate price for.

As Jacquez Green reflects on recent discoveries regarding the neurological epidemic that has plagued football, a game he started playing at the age of eight, he blanks.

“Right now, what we have found out is… See? like right then I was talking and my train of thought just left me just then,” Green said. “That happens a lot with a lot of guys who have ‘issues’ with their brains.”

Green, who played wide receiver, was recently inducted into the University of Florida Athletic Hall of Fame, having won a National Championship, among other honors during his tenure as a Gator. He was drafted in 1998 to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and would later play for the Washington Redskins and the Detroit Lions.

Despite a decorated eight-year collegiate and professional career, he hesitated when asked whether or not he would do it all over again, knowing what is known about brain injuries.

“I don’t know. I hear a lot of guys say they would, but I don’t know. When you’re young, you don’t care about anything; you think you’re gonna live forever, you think you’re gonna do everything,” Green said. “But as you get older you have issues and you’re not living the way most 40-year olds live.”

In December, the NFL met with the Players Association and agreed upon changes to the concussion safety protocol. A key change was the presence of an unaffiliated neurotrauma consultant on the sideline. Additionally, players who undergo in-game concussion evaluations will be subject to a follow-up evaluation the next day.

But the NFL wasn’t always this way. Safety has only recently become a priority.

“I played in games with guys with concussions, so it was thought of as just a part of the game,” Green said. “You never knew any long-term impacts about it. You got banged in the head, you just dizzy a little bit. Once you got back okay, you’d just go back in the game.”

In the past, players, coaches and the League largely ignored the effects of brain trauma – the league paid heavily for its disregard, denial and deception.

“I think in the beginning they were trying to silence it, but so much studies are out there now and so much of it is scientific, proven that they can’t really silence it as much,” Green said.

The high-profile suicide of Junior Seau in 2013, who was later found to have CTE, brought to light the danger and reality of brain injuries in former NFL players.

After great controversy and years of litigation, a billion-dollar settlement was reached between the NFL and thousands of former players who brought forward a lawsuit regarding brain injuries suffered while playing football. The money is meant to compensate players, fund research and cover medical exam costs.

Tykes in helmets and experimental tests

Now that all parties acknowledge the correlation and are aware of its effects, the next step is treatment and prevention.

“Prevention doesn’t seem likely if a person decides to bang their head over and over again,” Rebecca Carpenter, director of Requiem for a Running Back, said. “Cure, with biomarker technology and other things in the works, there may be possibilities in the next five to ten years of identifying ways of stopping the chemical cascade that takes place in response to brain trauma, but there are all kinds of challenges with that.”

Carpenter, the daughter of former NFL running back Lewis Carpenter, directed a documentary that dives into the history of the degenerative cognitive disease that affected her father and thousands of other men.

Presently, CTE can only be diagnosed after death, but Dr. Bennet Omalu, depicted by Will Smith in the 2015 film Concussion, identified the first ever case of the disease in a living person: Fred McNeil. Omalu was the first to discover CTE in football players. The experimental test used a radioactive tracer known as FDDNP which binds to tau protein and highlights them on PET scans.

Omalua is working toward a concrete test, which could potentially diagnose CTE prior to death, as he did with McNeil. He believes a test can be available within five years, which would be a monumental breakthrough in the field.

It may not prevent CTE development, but delaying football careers until high school gives children time to develop. Former players, researchers and neurologists agree that kids should not be playing tackle football and suffering concussive and sub-concussive hits so early in life.

“I am definitely in the camp of delaying tackle football until ninth grade, and using ages 5-14 to develop fitness, athleticism, teamwork, and goal setting capabilities,” Carpenter said.

Naturally, this sentiment was met with resistance. The Pop Warner football program voiced its disagreement with recent Illinois legislation passed prohibiting tackle football for children under 12 years old.

Football and the future

Though not as tragic as Seau’s suicide, San Francisco 49ers rookie linebacker Chris Borland’s retirement in 2015 once again put the NFL in the hot seat. Then 24 years old, Borland called his career off early, citing concerns about the long-term effects of repeated head trauma. He had suffered just two concussions in his career – both came before his college career – and was set to become an integral part of the team’s defense, but ultimately made the decision to step away from the game.

Situations like Borland’s spell trouble for the NFL. If a player in his prime is willing to retire, that sentiment may resonate with parents across the nation, steering their children toward sports that do not inflict brain damage.

“CTE is a cunning and baffling and horrifying disease.” Carpenter says. “I hope that amateurs who choose to participate moving forward do so judiciously, because the sport brings no guarantees, and when you are no longer winning, or no longer participating, the sport appears to have no use for you and no support for when you become symptomatic. You will be on your own.”

The destruction of gray matter was once a gray area in football, but research and legal action brought to light the dark truths of the sport. The National Football League is facing a blitz on its future and it is fourth down.